Lo último en la avenida

Francis McKee

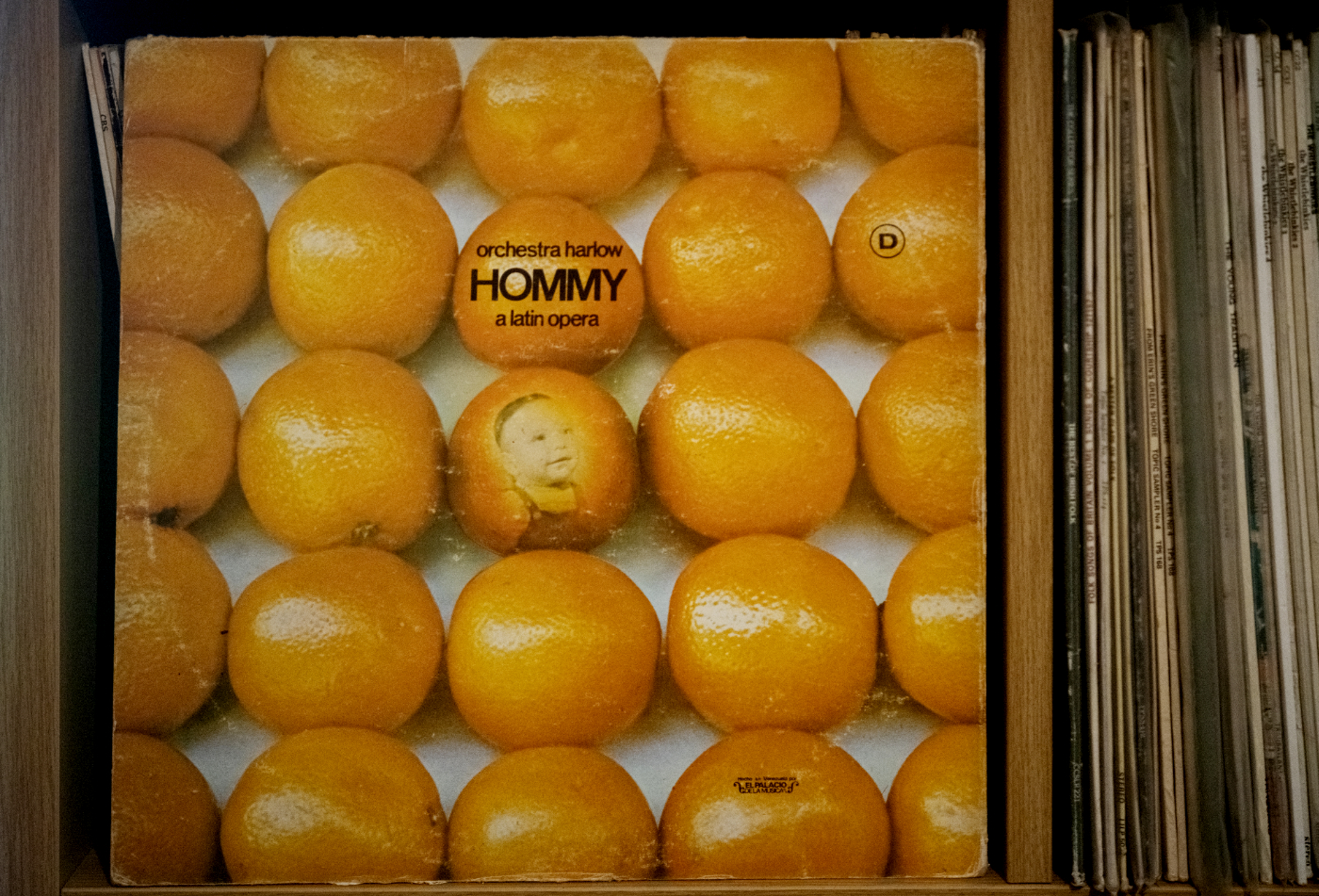

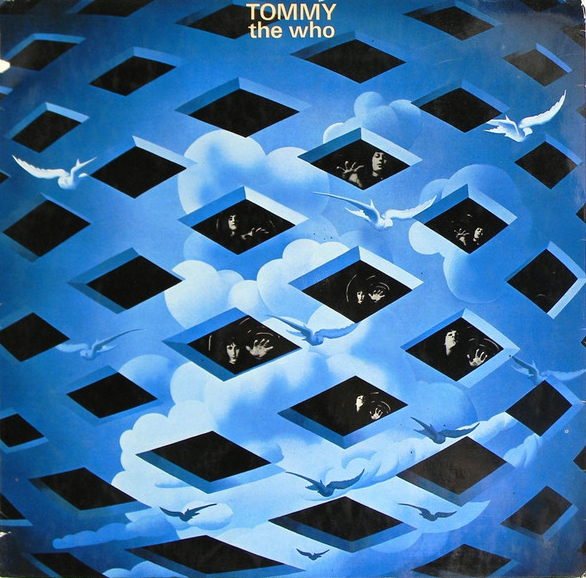

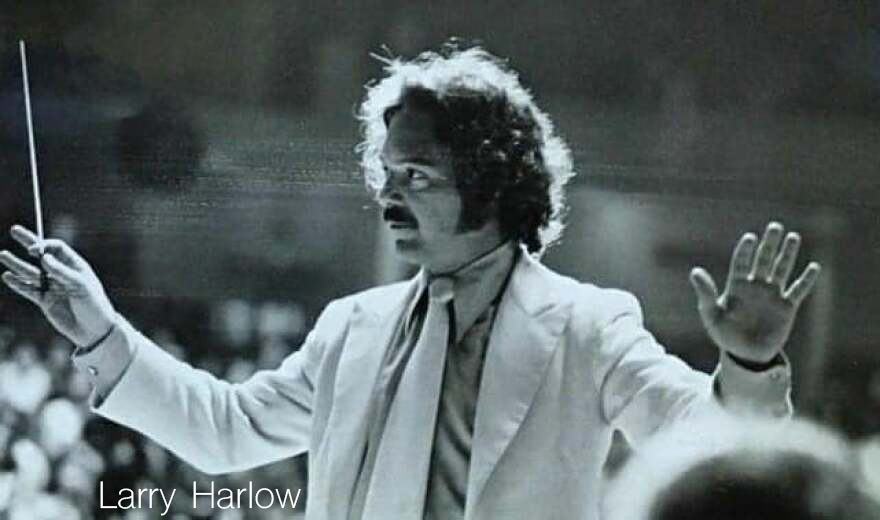

In 1973 Larry Harlow premiered Hommy, a Latin Opera at Carnegie Hall in New York. It was based on The Who’s Tommy and it mirrored the plot of the English rock opera in many ways: both works begin with the birth of a boy – ‘It’s a boy’ by The Who echoed by ‘Es un Varon’ by Harlow. Both children in the opera are deaf and blind and both reveal extraordinary talents – a pinball wizard in Tommy, a sensational percussionist in Hommy. The musical development of both works is also similar, the plot lines shadow each other and the songs often mark similar moments in the development of the characters. Hommy’s record sleeve, 1 with its rows of oranges, are a cheeky reminder of the Op-Art painting on Tommy’s cover and it’s a useful entry point into an exploration of the multiple dialogues embedded in Salsa albums of the time.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In 1973 Larry Harlow premiered Hommy, a Latin Opera at Carnegie Hall in New York. It was based on The Who’s Tommy and it mirrored the plot of the English rock opera in many ways: both works begin with the birth of a boy – ‘It’s a boy’ by The Who echoed by ‘Es un Varon’ by Harlow. Both children in the opera are deaf and blind and both reveal extraordinary talents – a pinball wizard in Tommy, a sensational percussionist in Hommy. The musical development of both works is also similar, the plot lines shadow each other and the songs often mark similar moments in the development of the characters. Hommy’s record sleeve, 1 with its rows of oranges, are a cheeky reminder of the Op-Art painting on Tommy’s cover and it’s a useful entry point into an exploration of the multiple dialogues embedded in Salsa albums of the time.

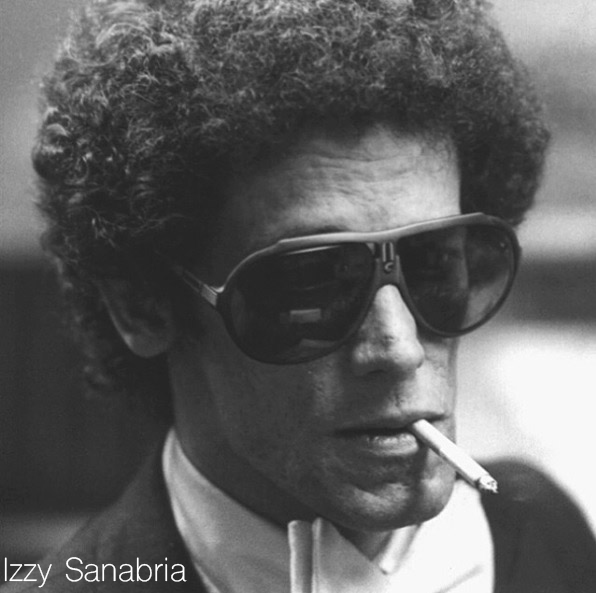

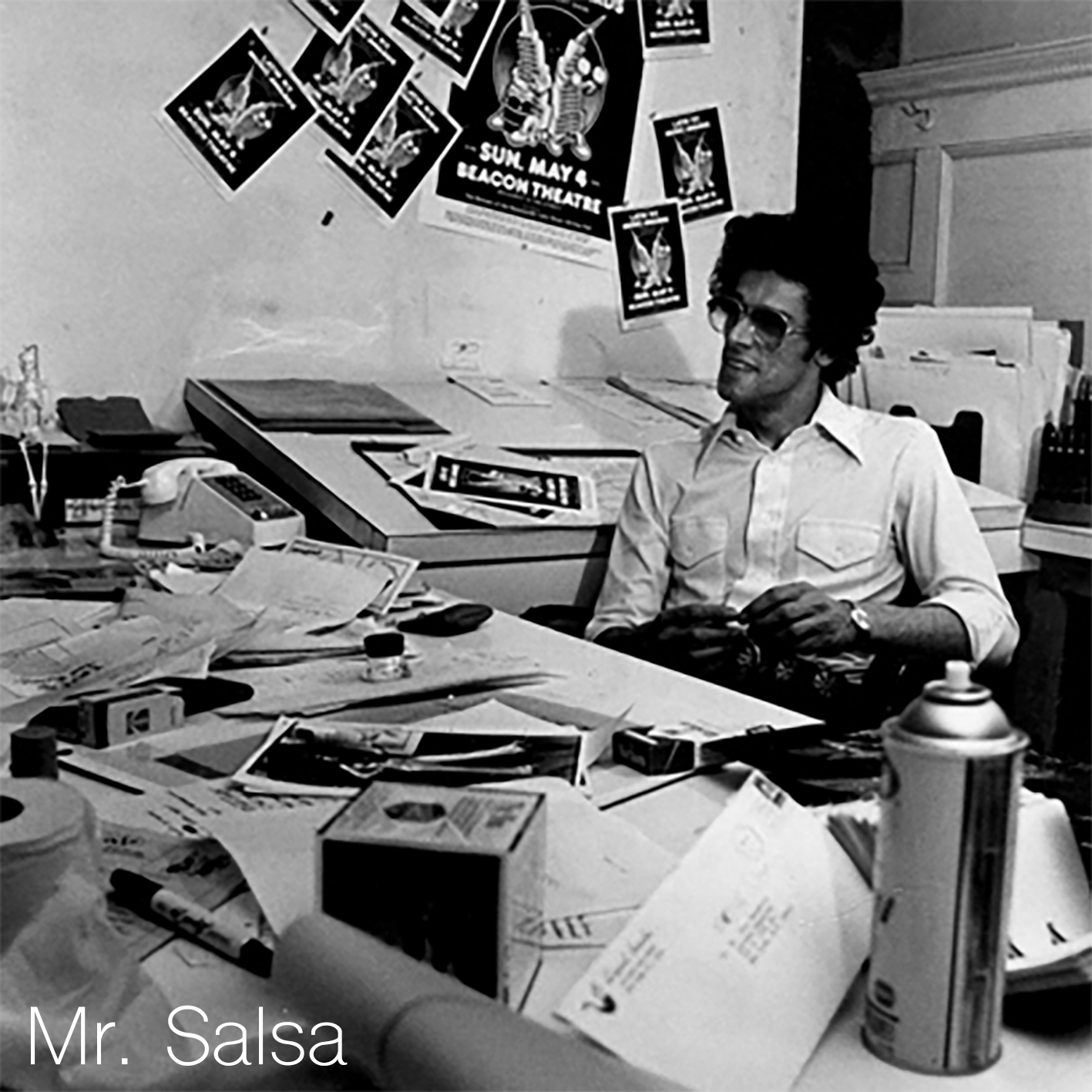

That cover of oranges was the work of Israel ‘Izzy’ Sanabria, probably the best known designer of Salsa albums and a formidable populariser of the term ‘salsa’ when he hosted a TV show of the same name in 1973. Sanabria’s career spans the early rise of salsa music in the 1960s through its heyday in the 1970s. Along the way, many of his designs became landmarks in the evolution of images that came to define the experience of something more than just music – a social and spiritual awakening in which music was inextricably linked to social change. His first cover was for Johnny Pacheco’s Pacheco y su Charanga (1961), the first album by the artist who would go on to found Fania Records in 1964 and sign most of the greatest salsa stars. It immediately set a high bar for others, evoking a hand-made woodcut with echoes of Africa, as stylish as any jazz album. Sanabria describes it as ‘… like a woodcut of Pacheco, and it captures him perfectly in all his skinny, energetic essence. To this day, he wears that image made in gold, around his neck. . . . The little imperfections and extra lines in it gave the whole thing an electrical movement, which is the way he moved on stage.’ It was iconic, elevating Pacheco and his music to a mythic level. And it was ahead of its time. The next Pacheco album - Pacheco y su Charanga Vol.2 – released in the same year had a Ben Perlman photograph of the full band, gathered in forced jollity around a horse, presumably ‘horsing around’. It feels antiquated beside the earlier cover, the banal product of an outdated marketing strategy.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Sanabria and some of his peers sensed there was a possibility for deeper expression in the medium of the LP cover. They were not alone in this. The recording industry as a whole was beginning to open up to new aesthetic approaches. As early as the 1930s Columbia Records had realised the sales potential of images under the pioneering hand of a young Alex Steinweiss. A budding graduate of Parsons School of Design, Steinweiss had learnt from the style of European poster artists and worked with Lucian Bernhard, a German forced to flee to New York before the war. Working for Columbia, Steinweiss saw that they were producing packages of 78 rpm records in plain pasteboard albums – ‘tombstones’ as he described them. He suggested that they decorate these dull sleeves with images that reflected the music inside and initially they rejected the idea, citing higher production costs. Eventually they permitted him to design a few trial covers and when an edition of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, originally clad in plain grey cloth, was released with one of his designs, sales leapt by 894 per cent. The point was made.

![]()

![]()

Sanabria and some of his peers sensed there was a possibility for deeper expression in the medium of the LP cover. They were not alone in this. The recording industry as a whole was beginning to open up to new aesthetic approaches. As early as the 1930s Columbia Records had realised the sales potential of images under the pioneering hand of a young Alex Steinweiss. A budding graduate of Parsons School of Design, Steinweiss had learnt from the style of European poster artists and worked with Lucian Bernhard, a German forced to flee to New York before the war. Working for Columbia, Steinweiss saw that they were producing packages of 78 rpm records in plain pasteboard albums – ‘tombstones’ as he described them. He suggested that they decorate these dull sleeves with images that reflected the music inside and initially they rejected the idea, citing higher production costs. Eventually they permitted him to design a few trial covers and when an edition of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, originally clad in plain grey cloth, was released with one of his designs, sales leapt by 894 per cent. The point was made.

Unfortunately, this development was restricted in the 1950s to classical music and jazz (by then perceived as something more cerebral than earlier Dixieland and swing bands). The jazz album covers were experimental and pushed the whole genre in exciting directions. Following the lead of Alex Steinweiss, designers looked to avant-garde European artists for inspiration. Considering these developments in the wider context of post-1945 global shifts of power, it possible to see the ways in which European contemporary art of the time was feeding into the emerging American dominance of the Western art world. Abstract Expressionism was on the ascent and bebob jazz, with its complex improvisations, was amenable to interpretation through new graphic and abstract images. It’s also worth remembering that while Jackson Pollock was being supported by the CIA, jazz pioneers such as Duke Ellington and Count Basie were being promoted on international tours that shadowed the geographical contours of the cold war. This led to interesting tensions between the aims of the United States support of these art forms and the subversive content of much of the art itself. For the state organisations however, this also reinforced the basic aims of their soft power strategy against the Soviet Union. Historian Lucie Levine points out that

President Truman personally considered Modern art, “merely the vaporings of half-baked lazy people.” But he did not declare it degenerate and expel its practitioners to gulags in Siberia. Not only that, abstract expressionism in particular was a direct repudiation of Soviet Socialist Realism. Nelson Rockefeller liked to call it “Free Enterprise Painting.”

In contrast to the Soviet Union’s “Popular Front,” the New Yorker magazine wonderfully, and perfectly, referred to the political role of American Modernism as “The Unpopular Front.” The very existence of American Modern Art proved to the world that its creators were free to create, whether you liked their work or not. 2

And in an article on CIA policy in the early cold war years, James Dillard lays out a more detailed analysis of how the very musical structures of jazz were integral to the cultural impact it would generate:

While Conover shunned overt propaganda, he believed deeply in the political and cultural importance of jazz. He described jazz as “structurally parallel to the American political system,” an embodiment of American freedom. “Jazz musicians agree in advance on what the harmonic progression is going to be, in what key, how fast and how long, and within that agreement they are free to play anything they want.” For people behind the Iron Curtain, he said, “jazz represents something that is entirely different from their traditions.” Conover believed that people who were denied freedom in their political culture could detect a sense of freedom in jazz. He asserted, “Jazz is a cross between total discipline and total anarchy. The musicians agree on tempo, key and chord structure, but beyond this everyone is free to express himself. This is jazz. And this is America. That’s what gives this music validity. It is a musical reflection of the way things happen in America. We are not apt to recognize this over here, but people in other countries can feel this element of freedom. They love jazz because they love freedom.” 3

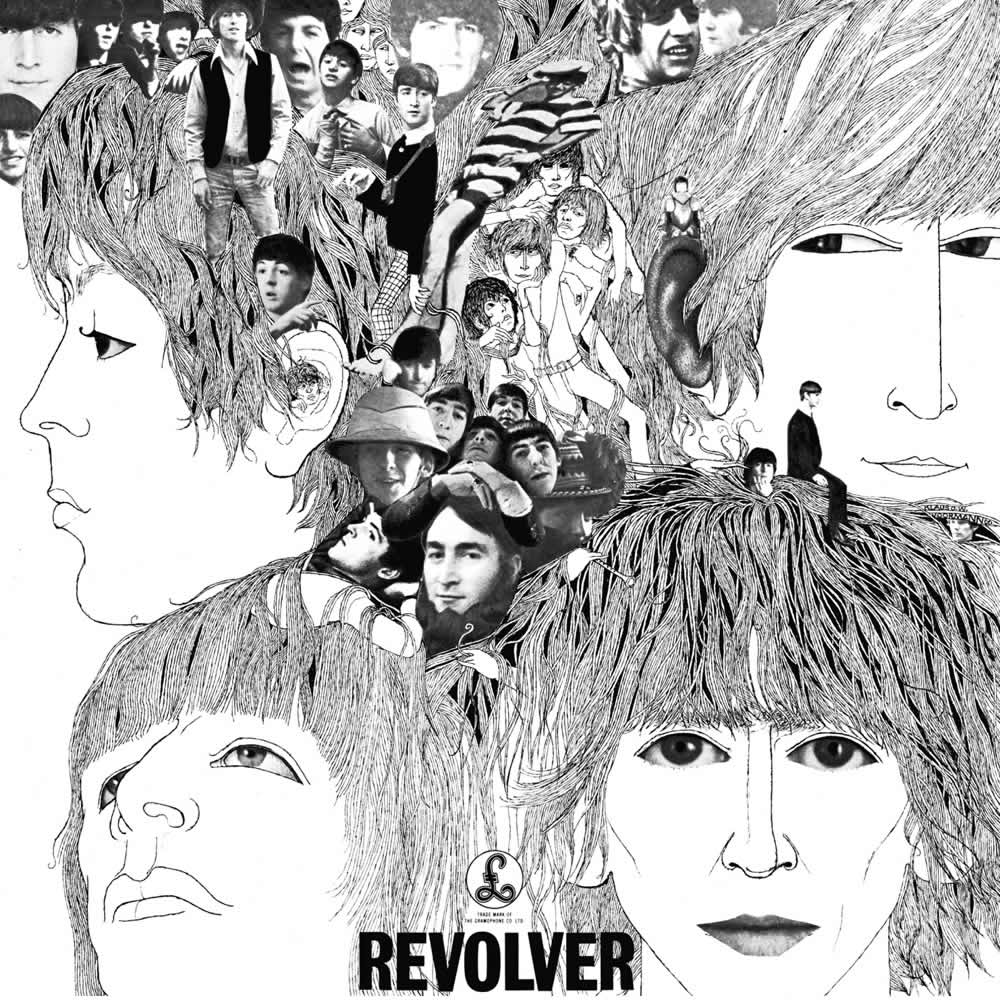

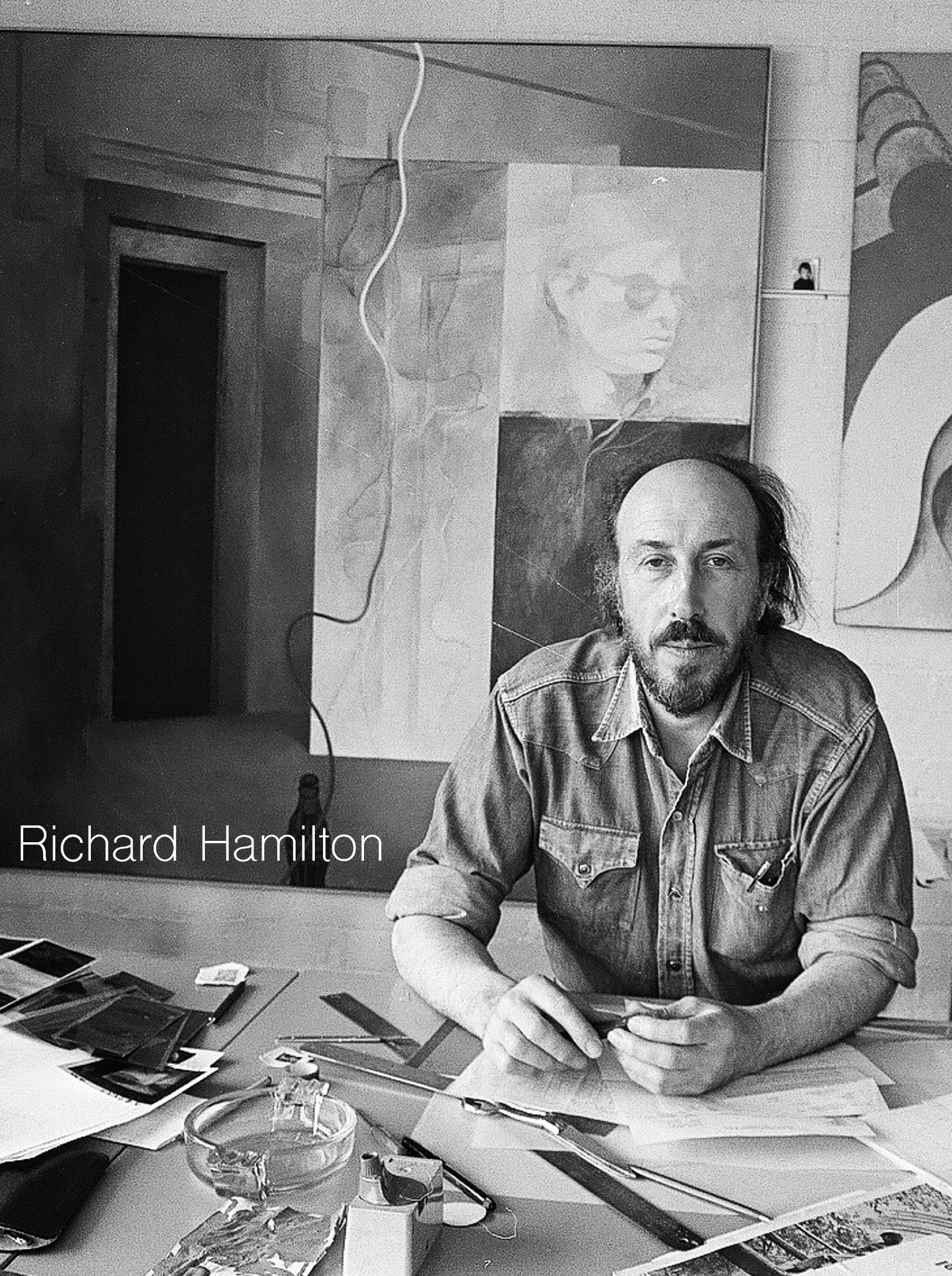

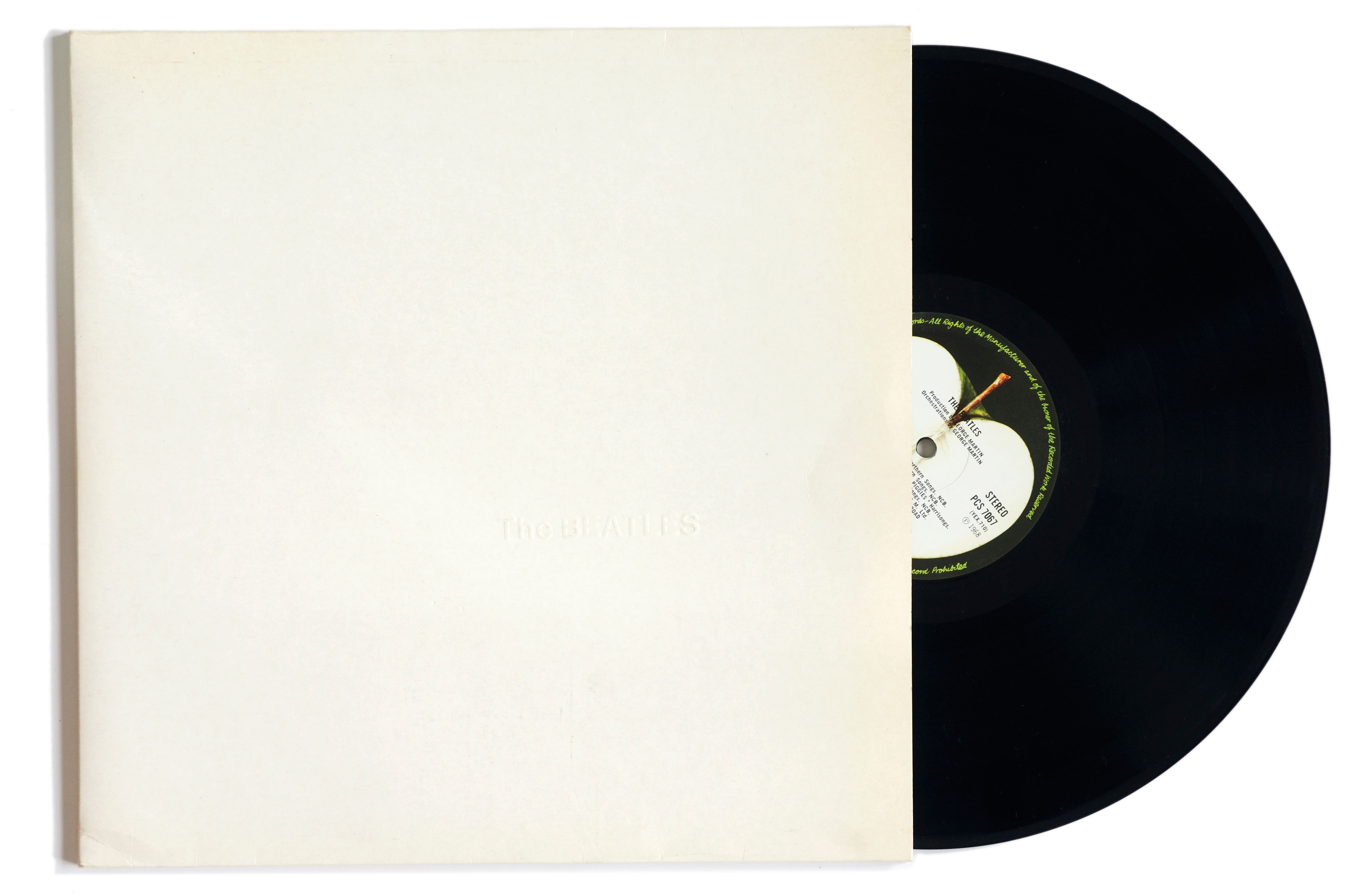

This was the context that also rippled through the development of Salsa music – issues of race, politics and religion would all be played out in the creation, distribution and reception of the music. The album cover would come to play a vital role in this process. Just as jazz embraced abstraction and modernism in its album covers, Salsa would invoke images that could articulate the emerging political and cultural consciousnes of Caribbean and latin-american communities. That did not happen overnight and as Johnny Pacheco’s charanga albums demonstrated, one step forward could be countered quickly with another step backward. While jazz was perceived as increasingly intellectual, music such as boogaloo in the 1960s faced the same uphill struggle as emerging rock and pop. Rock and roll albums suffered from generic band photos until the Beatles began to push for control of their own covers. Always a cut above the others in the UK, Beatles album images really started to blossom on Rubber Soul (1965) and Revolver (1966). Most importantly, though, they commissioned the artists Peter Blake and Richard Hamilton to create covers for Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band (1967) and The White Album (1968). The floodgates opened after that as musicians and astute record labels saw the benefit of an album jacket summarising the ethos of a younger generation. Collaborations with artists suddenly seemed possible as an equally unruly wave of pop and conceptual artists did not recognise the intellectual and implied class distinctions of jazz and classical. Pop, rock and radical were in tune with the new aesthetics of the 1960s and beyond. One artist, perhaps more than any 4 other, perceived the opportunity now on offer. Andy Warhol, the Pittsburgh factory builder who understood the democratic power (and market influence) of mass manufactured items such as Coca Cola bottles, Brillo Boxes and Campbell’s Soup cans, immediately grasped the significance of the 12” x 12” canvas. That painter of icons could easily engage with the album cover and have his new icons (The Velvet Underground & Nico, The Rolling Stones, Thelonious Monk, Count Basie, Aretha Franklin, John Lennon, Diana Ross, Lisa Minelli et al) industrially distributed to an audience who might never consider entering a gallery.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

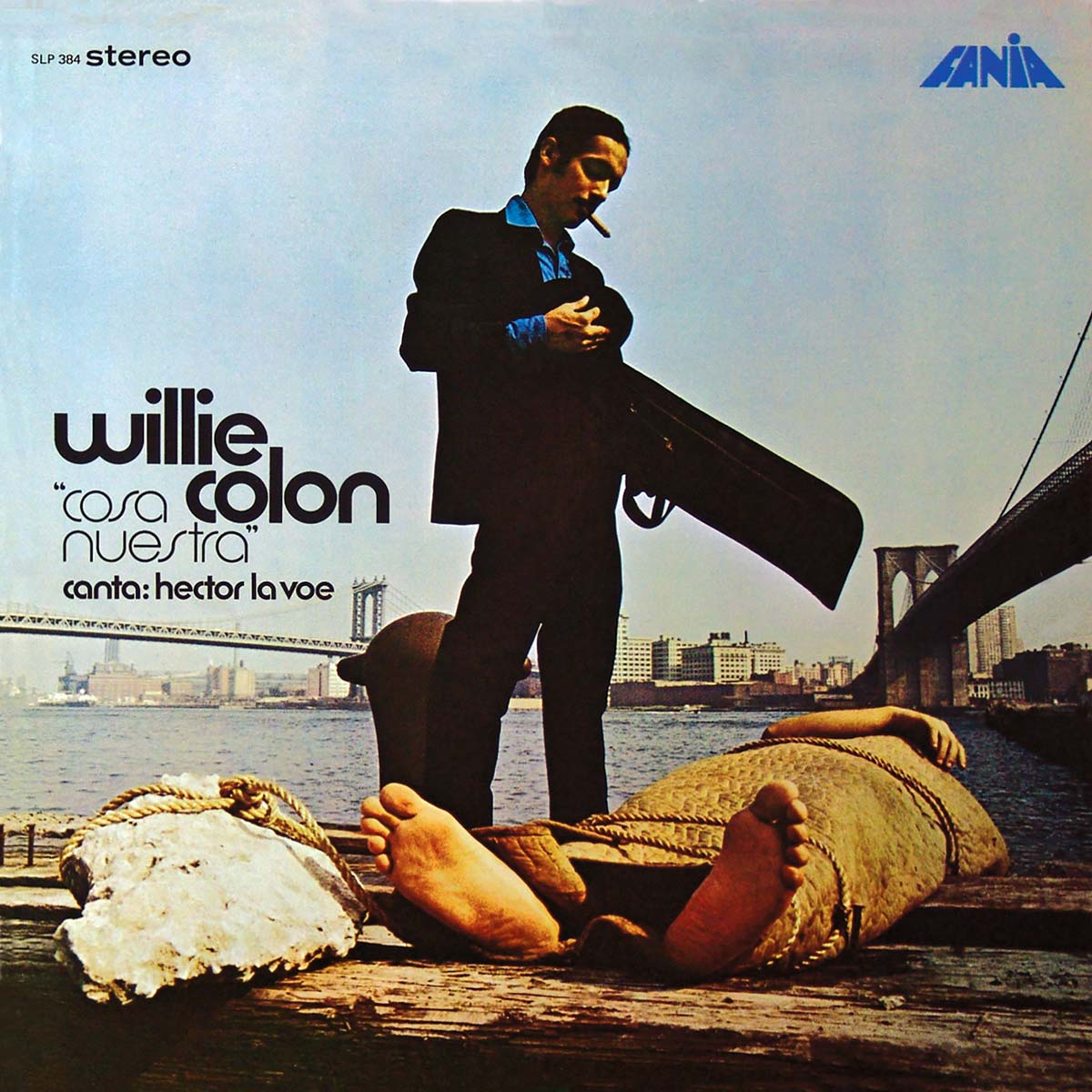

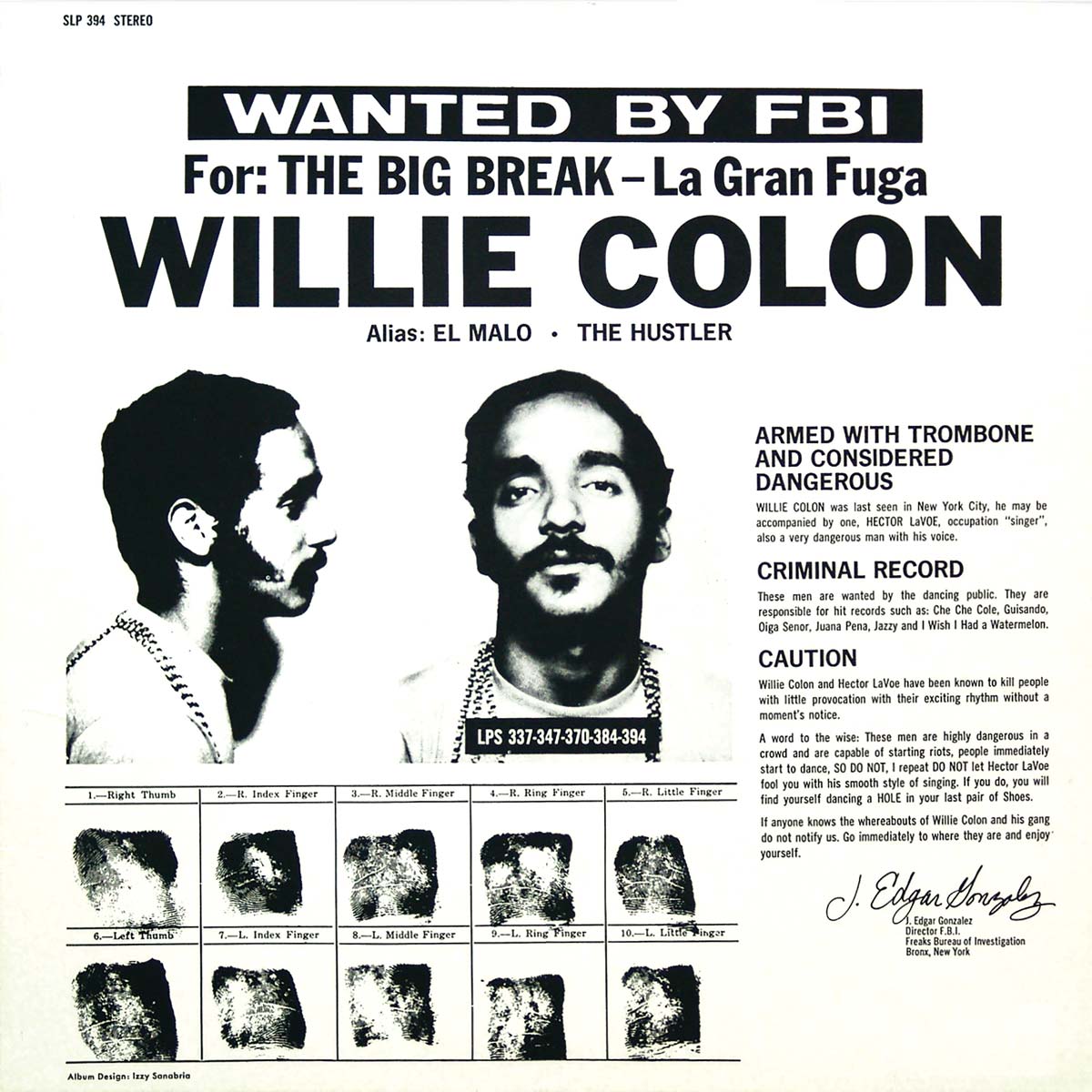

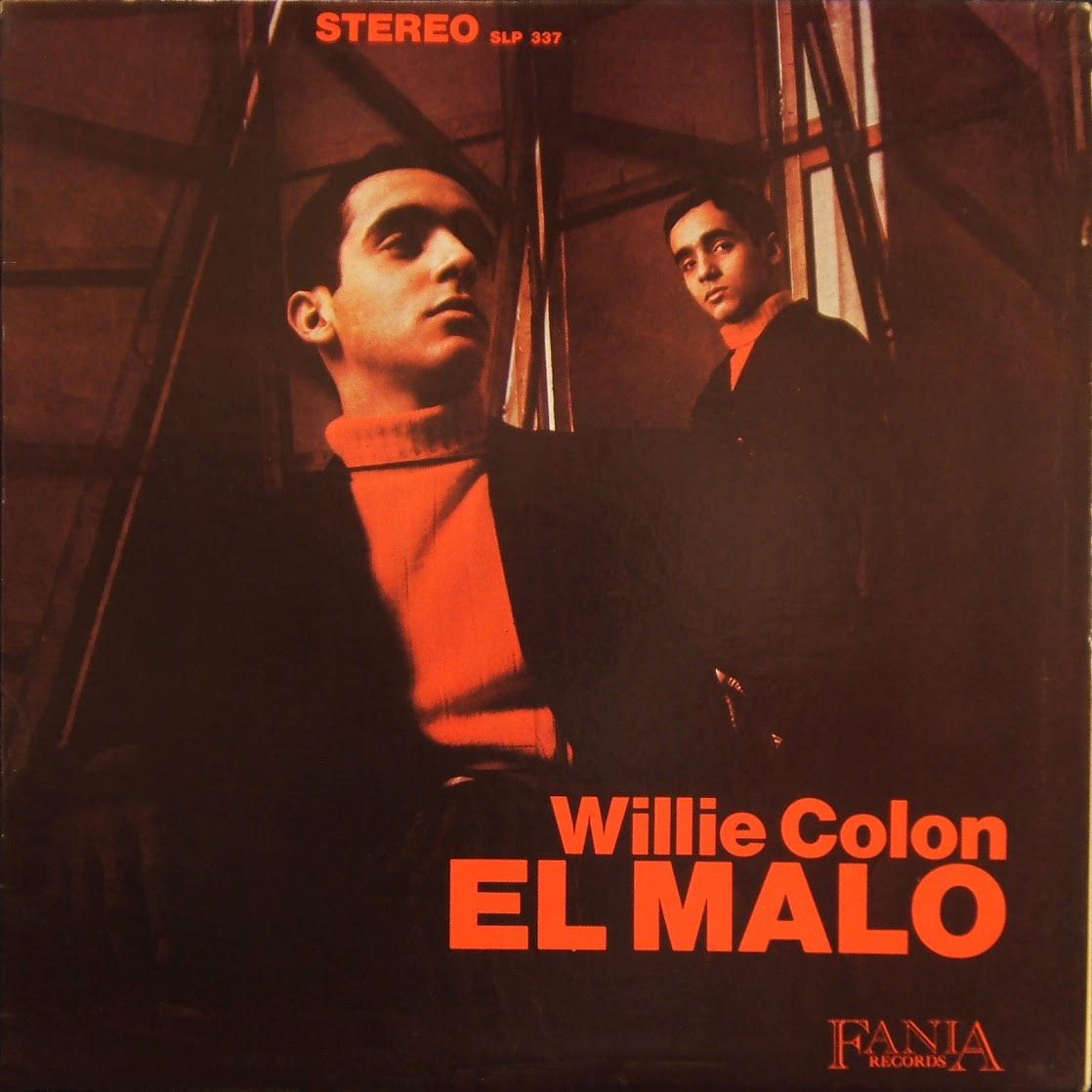

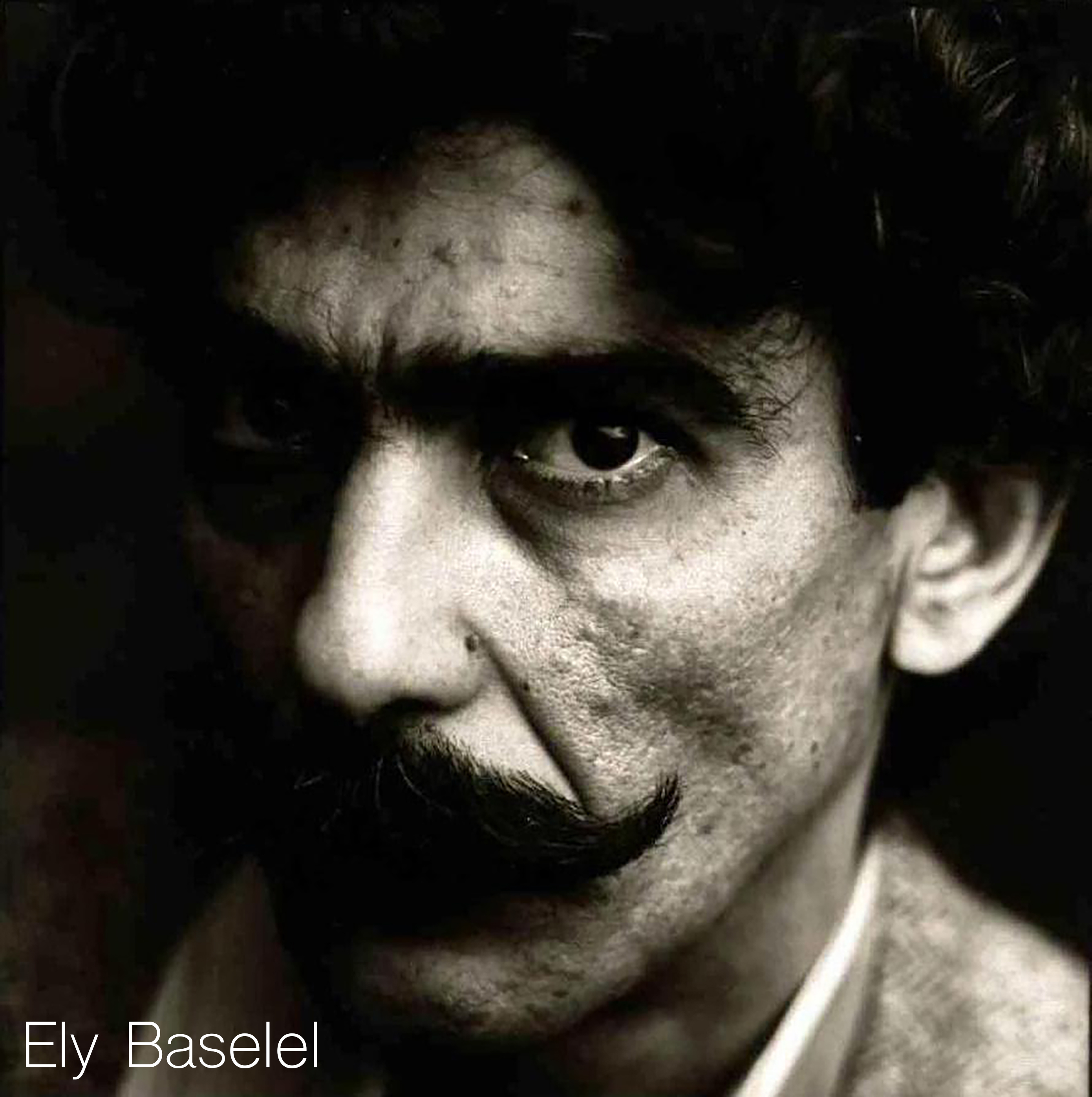

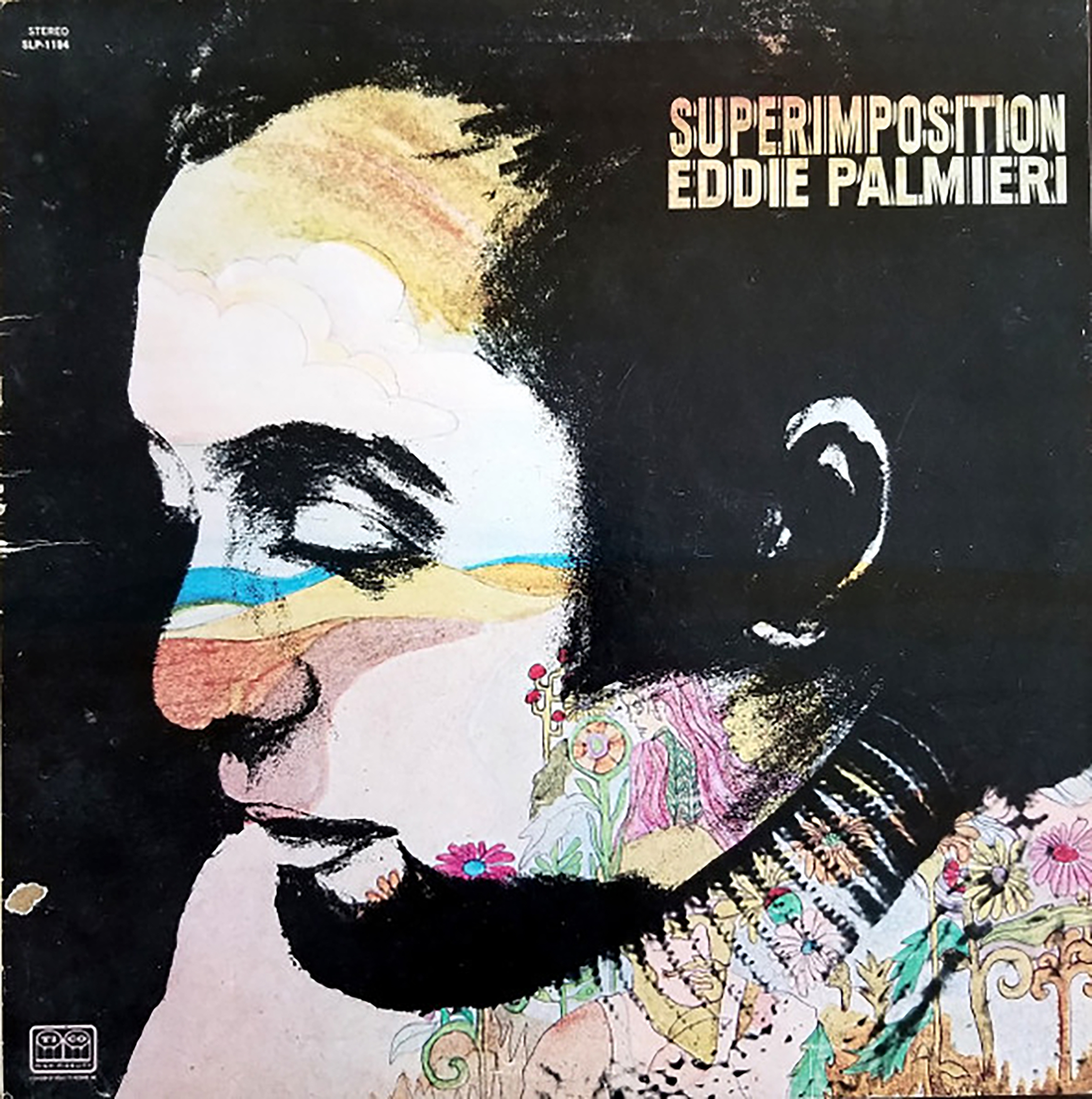

Izzy Sanabria, designing for Fania, and Ely Besalel, designing for Tico, immediately saw the possibilities: not just the creative opportunity to escape the bland band photos and the deluxe ‘exotic’ dancer covers, but the potential to articulate social issues, to link the music inextricably to the surging sense of emergence and change in their communities. For Sanabria that manifested itself in a magnificent sequence of covers that included Willie Colon’s Guisando, El Malo, The Hustler, Cosa Nuestra, La Gran Fuga, El Juicio and El Malo not to mention landmark covers such as Power, Indestructible, and, Acid and Rican/ Struction for Ray Barretto. And for his friend and rival, Ely Besalel there was an equally impressive string of covers that included Joe Cuba’s Bustin’ Out, Ismael Rivera’s Esto Fue Lo Que Trajo El Barco, and Lo Ultimo En La Avenida, Rafael Cortijo’s Cortijo Y Su Maquina Del Tiempo, Tito Puente’s On The Bridge, La Lupe’s La Lupe Es La Reina, and Eddie Palmieri’s Vamonos Pa’l Monte, Justicia, and Superimposition. Sanabria and Besalel were working among a host of other talented designers such as Charlie and Yogi Rosario, Acy Lehman, and Ron Levine. Sanabria’s work drew on wider cultural dialogues – with rock music imagery, films (The Godfather, Blaxploitation), superhero comics, psychedelia and contemporary art (Dali, surrealism). Besalel sometimes stayed closer to reality, the materiality of the street and the urban landscape of New York inform some of his best covers and their immediacy conveys the hard swing of the music inside the jacket and the feedback loop between the players and communities.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

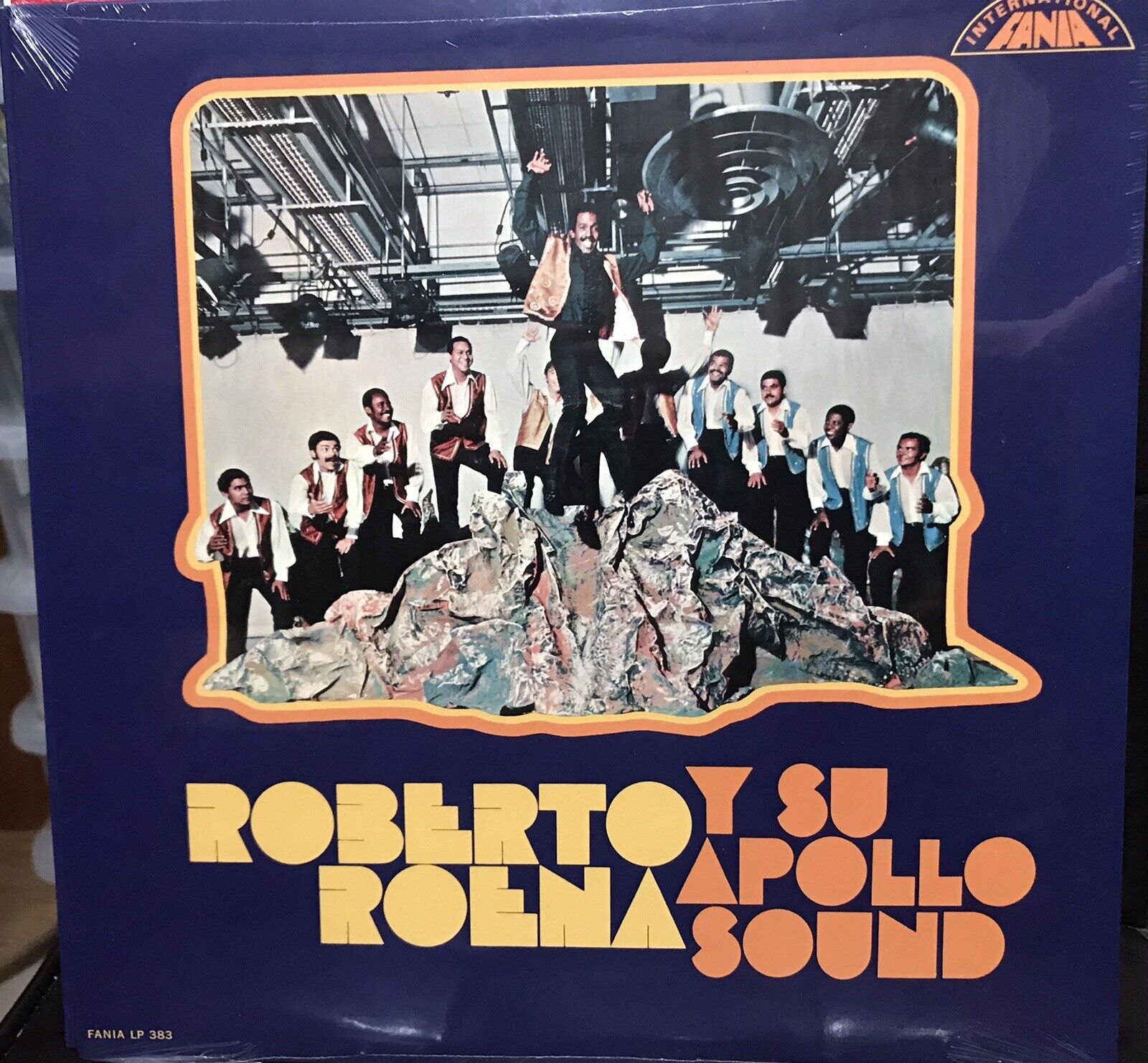

The politics of those communities also permeates these images. Sanabria’s parodies of gangsters and the justice system in covers such as La Gran Fuga (actually censored by the FBI) and Juicio speaks to the stereotypes of the barrio while Willie Colon, still a teenager when he recorded his first three albums) defiantly mocks that system. His Barretto jackets created a percussionist Superman, a musical saviour, much like the hero of Harlow’s Hommy. Albums by Eddie Palmieri often focused the audience on racial inequality, particularly from Justicia through to Harlem River Drive. These were communities that still experienced colonisation or who existed in exile after anti-colonial revolutions. While the albums from the late 1960s through to the mid-1970s reflected countercultural and radical influences on their design there was also a longer history of covers that dealt more satirically with colonial politics. Many Puerto Rican and Cuban records portrayed the musicians dressed for travel, suitcases at the ready and preparing to head for the moon. The Cuban group,Orquesta Aragon’s Me Voy Para La Luna is one of the best examples. The musicians, playing checkers, and toting a fishing rod, butterfly net, instrument cases and a clave pass the time waiting to board while a 1950s rocket soars towards the moon behind them. It’s unclear who is colonising who in this image though the harder economics underpinning it would have been clear to its audience. Those space covers continued through the more radical years, updating themselves in the wake of technological advances. In 1969, the year of the first moon landing, Roberto Roena y su Apollo Sound brought out their first album. The cover, by Ron Levine, places Roberta on reaching towards what appears to be a rocket engine though on closer inspection it turns out to be a very futuristic air conditioning unit. It may have been a more tongue-in-cheek tradition than the more mainstream afro-futurism of Miles Davis or Sun Ra but it’s desire for escape and the quest for a more equitable universe was no less serious. Interestingly, the title track of the Orquesta Aragon album identified the destination as a honeymoon and the journey was inward, away from society:

“Yo quiero pasar la luna de miel con mi único amor que llevo en mi ser y viajaremos a la luna para vivir en paz. Voy a descansar de tanta ambición,

vamos a vivir sin preocupación, allí seremos muy felices en nuestra soledad”.

This exploration of inner space and retreat from the stress of a capitalist world manifests itself in other forms too. Ely Besalel’s cover for Cortijo y su maquina del tiempo evokes a journey through time in several ways: across the traditions of Latin American music on the one hand and through other dimensions via the fluidity of the music’s time signatures on the other. Robert Farris Thompson wrote of the album in this way:

What I think I hear Rafael Cortijo saying, in his monumental LP “Cortijo & His Time Machine” (Coco CLP 108) would go something like this: “I shall honor my ancestors, their Kongo bomba rhythms from the north of Puerto Rico, but I shall also honor the individual dreams of my fellow Puerto Ricans in New York, adding to the fast tempo of the bomba a thousand reflections of what we learn and face and live in Nueva York—mambo, rock, son montuno, jazz, even the famous hi-dee-hi-dee-hi-deeho scatting of Cab Calloway, if I so desire. My music is a time machine and I will bring the past and present to a simmering boil over the tumbaos [bass riffing patterns] and guajeos [treble riffing patterns] of Afro-Cuban music. It will be Puerto Rico within Cuba within Nueva York within the world. We are on the move. You cannot stop us, let alone dictate academic boundaries.” 6

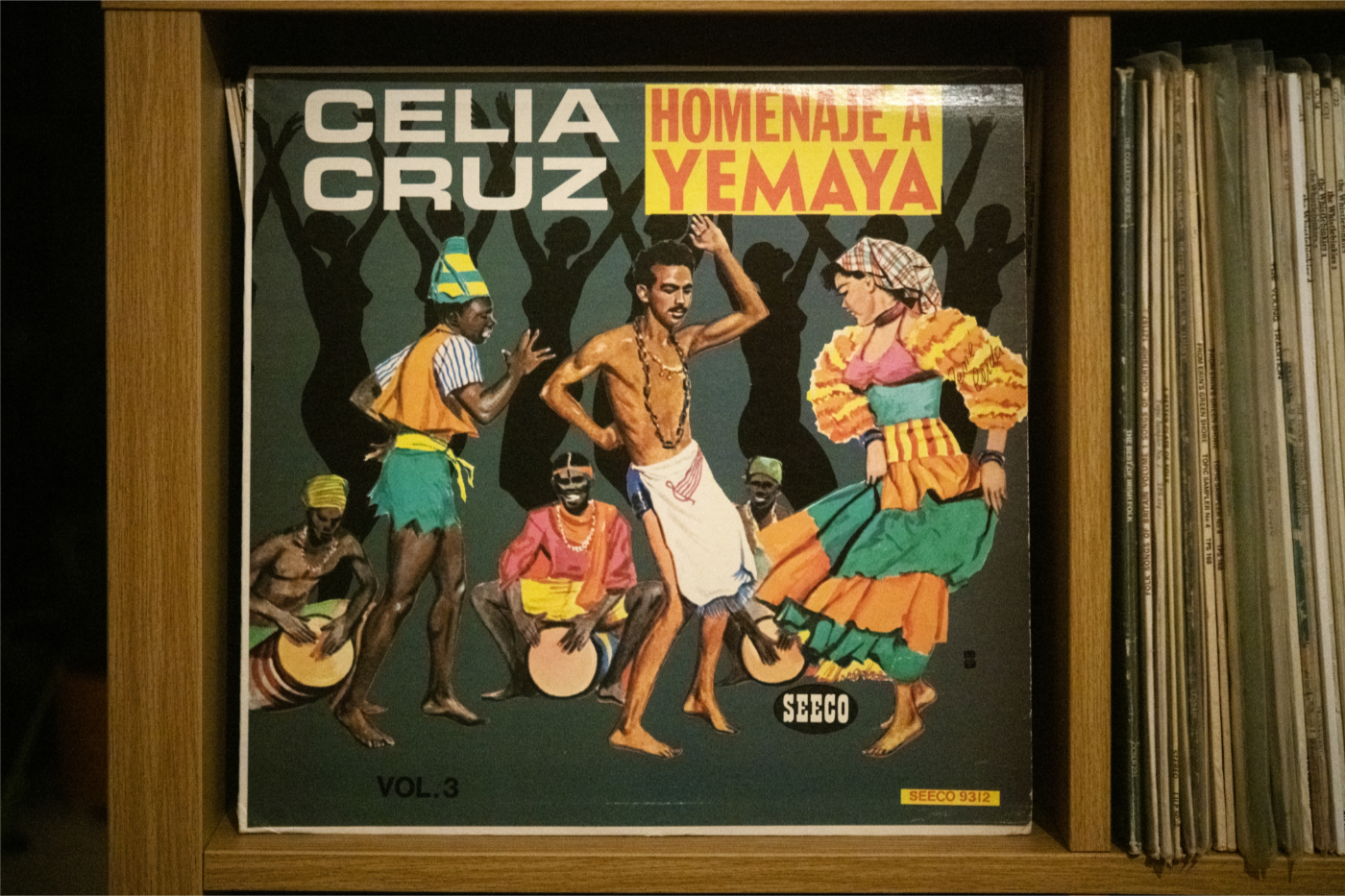

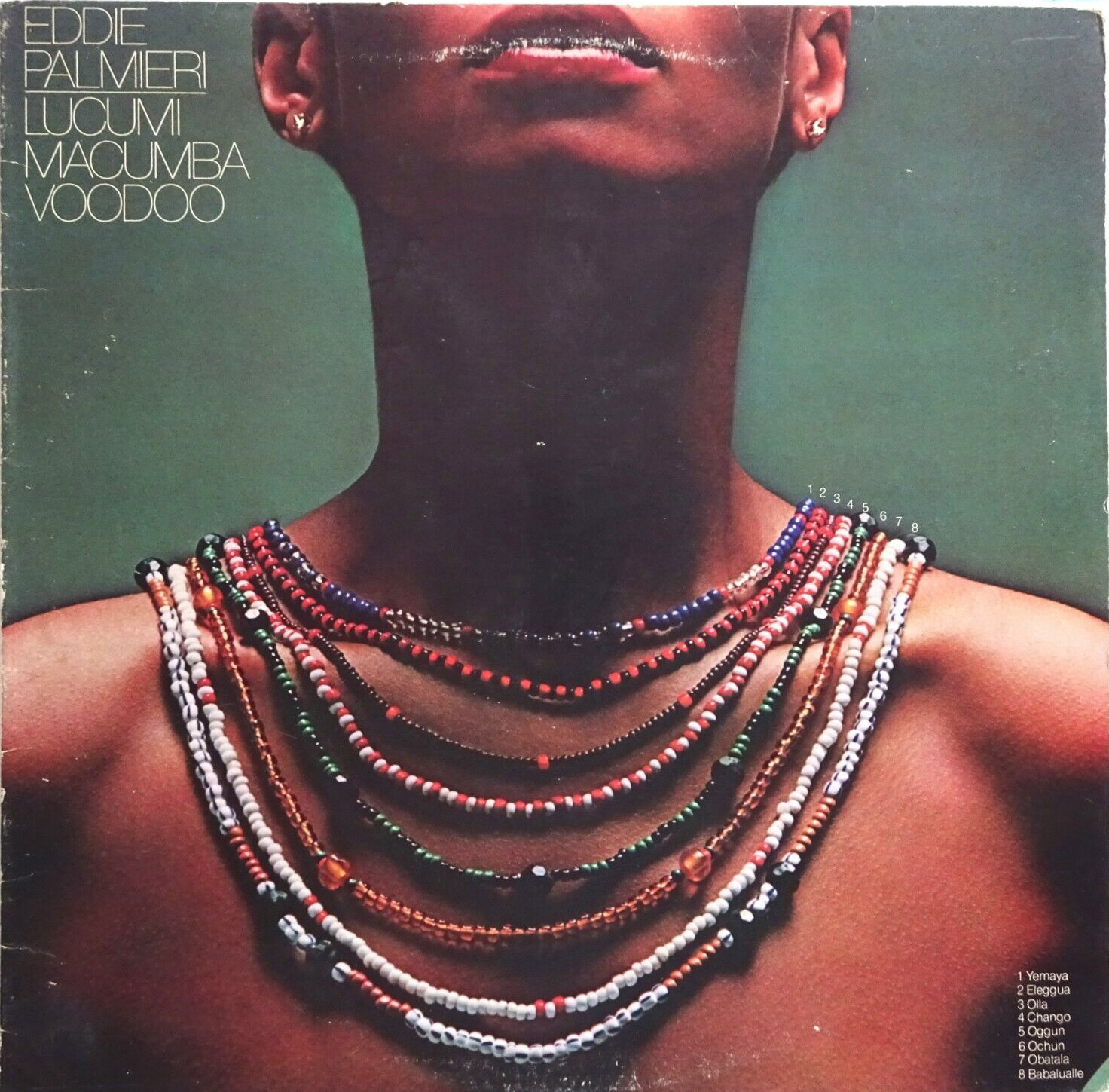

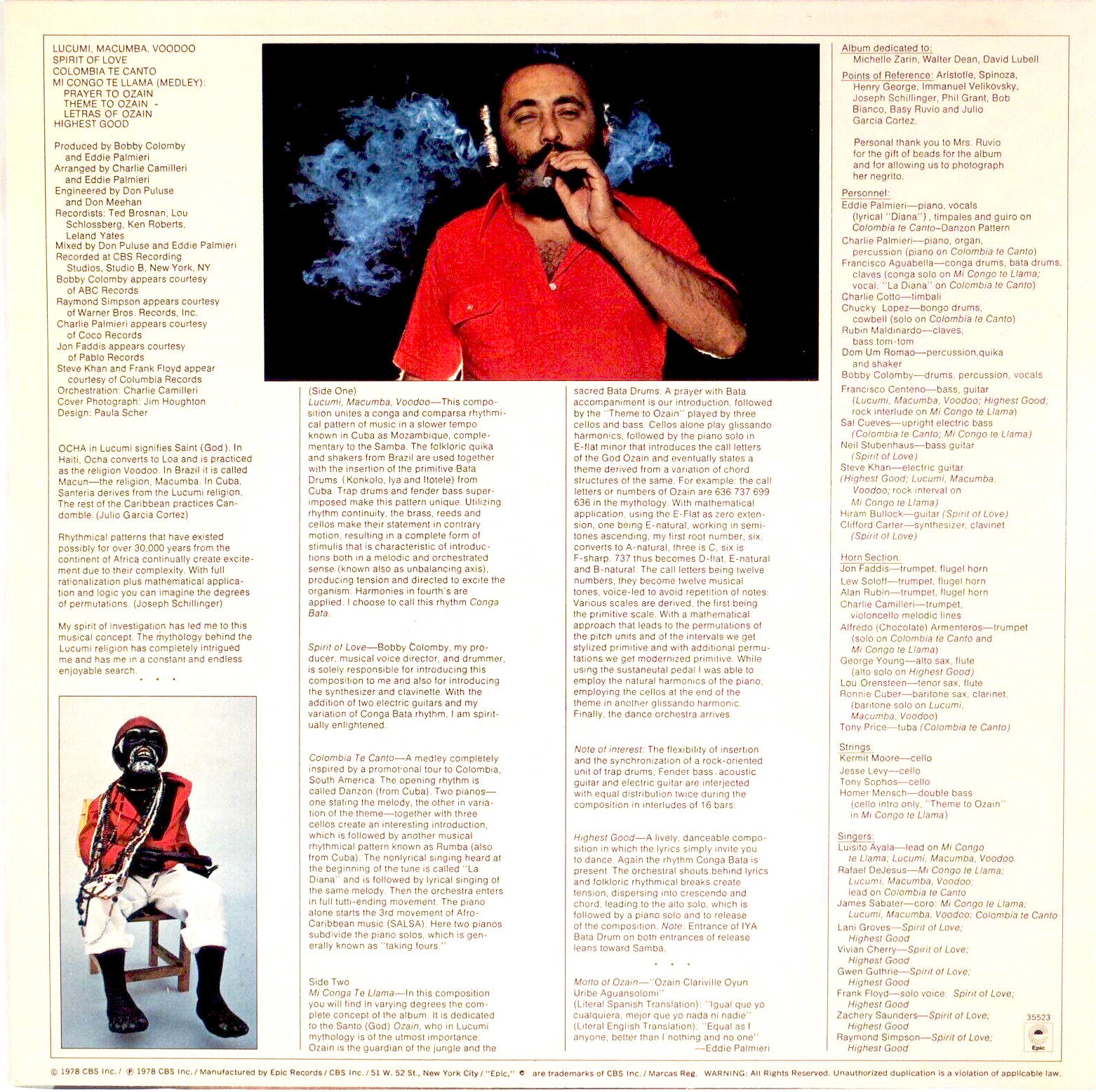

In the same article Thompson points to the Yoruba or Lucumi presence in the music of Cortijo, Barretto and Eddie Palmieri, something that remains to be examined in detail. That presence is always there but over decades the ways in which it appears changed radically. It is clearly present in the music of Celia Cruz and La Sonora Matancera. They made several albums of songs completely devoted to the Orishas - Homenaje a Los Santos (1964), Homenaje a Los Santos, Volume 2 (1965), and Homenaje a Yemayá (1971) while Cruz distanced herself in different ways from any direct confirmation that she was a follower of Santería. The covers of those albums also seemed ambivalent with elements of the traditional woodcut used by Sanabria in 1961 combined with figures close to cartoon caricature. By 1978 Eddie Palmieri was recording Lucumi, Macumba, Voodoo, an album that fuses references to the Orishas to music that touches on Palmieri’s earlier work but with a distinct flavour of rock and disco underpinning everything. The album cover, designed by Paula Scher, is a close up of a sensual model wearing a range of Santería necklaces, each carefully annotated. The liner notes point quickly to the Gods referenced before moving into a heavily mathematical analysis of the rhythms. This more upmarket, museological presentation manages to distance Palmieri from any committed statement of belief while foregrounding the impact of Santería on Latin-American culture.

In the same article Thompson points to the Yoruba or Lucumi presence in the music of Cortijo, Barretto and Eddie Palmieri, something that remains to be examined in detail. That presence is always there but over decades the ways in which it appears changed radically. It is clearly present in the music of Celia Cruz and La Sonora Matancera. They made several albums of songs completely devoted to the Orishas - Homenaje a Los Santos (1964), Homenaje a Los Santos, Volume 2 (1965), and Homenaje a Yemayá (1971) while Cruz distanced herself in different ways from any direct confirmation that she was a follower of Santería. The covers of those albums also seemed ambivalent with elements of the traditional woodcut used by Sanabria in 1961 combined with figures close to cartoon caricature. By 1978 Eddie Palmieri was recording Lucumi, Macumba, Voodoo, an album that fuses references to the Orishas to music that touches on Palmieri’s earlier work but with a distinct flavour of rock and disco underpinning everything. The album cover, designed by Paula Scher, is a close up of a sensual model wearing a range of Santería necklaces, each carefully annotated. The liner notes point quickly to the Gods referenced before moving into a heavily mathematical analysis of the rhythms. This more upmarket, museological presentation manages to distance Palmieri from any committed statement of belief while foregrounding the impact of Santería on Latin-American culture.

Both Cortijo and Rivera, though, express a longer term explicit belief in the world view of Santería. The covers of two albums they made together - Con Todos Los Hierros (1967) and Llaves de la Tradicion (1977) – present images that can be read on two levels. In Con Todos Los Hierros the two musicians pose behind a small mountain of tools (saws, mallets, wood planes etc) that reference the trades they followed in their early life. At the same time, an adept of Santería could read the image as a reference to Ogun, the Yoruba god linked to ironwork and smithing. Likewise, Llaves de la Tradicion presents an image of iron keys which for the initiated would again point to Ogun, the owner of keys and locks. These covers recall the syncretism at play in Puerto Rican culture where Yoruban gods are linked to Catholic saints, transforming Christian iconography into a fertile hybrid of ideas and beliefs where those gods could continue to be worshipped. While the Catholic Church might still only see their traditional saints, Santería offered a double vision to be read by those who knew how to do so.

![]()

![]()

For Ismael Rivera, this was such an important aspect of his album covers that it operates in several of his solo albums too. Vengo Por La Maceta (1973) presents us with a simple mortar and pestle though, again to initiates, it is likely to evoke the river goddess Oshun. And on El Ultimo En La Avenida (1971), where Rivera collaborates with Kako, Ely Besalel creates one of the most powerful album covers in the history of Salsa. It is a photograph of a shop window, probably in New York as we see tall skyscrapers in the far distance. It’s an upmarket women’s shoe shop and behind the display of shoes is the figure of a large gold and silver cockerel. In the window’s reflection we simultaneously two women, one looking at the shoes, the other striding past with determination. Behind them there is an arched entrance to an old church and above it, two stained glass windows. The reflections of the window fuse both inner and outer world into one image. The Christian church is flattened behind the large cockerel – sacred in Santería culture and linked to the orisha, Osun – while the broader image places both religions in the context of a more material, capitalist world.

![]()

![]()

Lo Ultimo En La Avenida is clearly a part of this material world – a cardboard jacket protecting a vinyl record designed to be displayed, like the shoes, in a show window or behind a counter. It is part of the wider, often overlooked, materiality of recorded music, a point well made by Elodie Roy in Media, Materiality and Memory:

The materiality of music is what ensures its durability and circulation across different spatiotemporal sites, as well as its archiving and preservation (music becomes a three-dimensional cultural product which can be simultaneously commodified). The tangibility of music, which allows for its future excavation and redemption, is itself always already haunted by past temporalities and moments. The original moment of recording, and the subsequent replaying of the record, allows us to think of the record as that which literally gives birth to ghosts. Media artefacts are both the place and the instrument of a return. 7

While this material is pertinent to all music in all cultures, it could be seen differently in some communities of Salsa listeners. In the case of El Ultimo En La Avenida, the record is one of several by Ismael Rivera who has gone to pains to highlight the wider context of Santería that surrounds his music. Not only that but Santería itself is a religion that prizes materiality. In an article on the materializations of oricha voice, Kristina Wirtz, argues that

A ritual lead singer demonstrates skill by skating the thin edge of danger in his or her improvised lines, as well as by managing the overall sequencing of songs and energy level of the music and other participants. That is, even beyond the lyrics themselves, more palpable dimensions are important, such as the volume and tempo of the music and the density of sonic textures produced not only by the interlocking drum rhythms, but also by people clapping and shouting, by the added ringing of bells … and by similarly direct measures of enthusiastic participation in the ceremony. Such features together constitute the effort to attract the oricha’s attention. Similarly, the invocations and prayers that initiate all ritual activity are necessarily accompanied by, and embedded in, material offerings that range from the most durable accoutrements of altars and sacred vessels to permanent gifts (such as decorative cloth, bells, bottles of alcohol, and statues), to more perishable offerings (such as cooked and baked foods, fruits, flowers, animal blood and organs, and fresh water), and even to such ephemera as a lit candle, smoke from a cigar, or a fine mist of rum sprayed from someone’s mouth. … Sounds, too, are material offerings as well as hailings. They include not only the full-fledged sequences of songs and rhythms in a festive ceremony, but also the more frequent ringing of a particular bell or shaking of a rattle to salute a particular oricha when approaching the altar. 8

It might not be too much to suppose that an album cover referencing a particular orisha could be taken as a material offering containing another offering – the music and song – within. Wirtz’s description of a lead singer ‘skating the thin edge of danger in his or her improvised lines’ while managing the ‘sequencing of songs and energy level of the music’ certainly evokes the skills of Maelo. And in the same spirit, Elodie Roy’s statement that ‘The original moment of recording, and the subsequent replaying of the record, allows us to think of the record as that which literally gives birth to ghosts’ takes on a new meaning when listening to this salsero summoning the past and creating new non-linear pathways through time. When Ivelisse Rivera was asked what her brother, Ismael, had meant by his famous repeated cry ‘Ecuajey!’ she replied ‘Claro. ‘Dios te bendiga’. No sé de dónde lo sacó, pero nos dijo que eso significaba. Él cuando llegaba a la casa decía: ecuajey. Y luego, cuando se iba, decía: écua. Así era él’.9 An admirer of Rivera’s music, Lorena Carolina, explained in more detail the ramifications of the phrase, its links to the orishas and its acknowledgement of their world:

Yo quiero aprovechar la oportunidad para compartir con ustedes la información que dejé la primera vez que hice referencia a esto, que es parte de una entrevista realizada a Ismael Rivera:

"Ecuajey" efectivamente ha sido reseñado en otras publicaciones e investigaciones como un saludo que se da a las puertas del cementerio, o a una deidad específica; se dice que es un vocablo Yoruba. No es una palabra inventada por el sonero aunque podemos decir que fue acuñada por él al ponerla en boca de los que le conocieron y los que aún le seguimos. Un caballero integrante del grupo dejó en comentario un tema de Benny Moré ( En el Tiempo de la Colonia) que data del año 1953 - en mi caso ya lo había escuchado - donde el cubano pronuncia la palabra "Ecuajey". Y para más señas el propio Maelo en entrevista radial realizada acá en Venezuela por el difusor de música caribeña Héctor Castillo refiere que es un saludo a las puertas del cementerio: "Bueno pues... en la religión santera Locumí eso quiere decir que cuando tú pasas por frente al cementerio 'Ecuajey yansa jey' quiere decir... yo sé que algún día de estos tendré que visitar tu morada...pero tú le estás dando el respeto y haciéndole saber que tú sabes que quieras o no un día de estos tendrás que ir a descansar ahí..." 10

In the The Recording Angel: Music, Records and Culture from Aristotle to Zappa (1987), Evan Eisenberg observed that ‘A record is a world; even its shape, unchanged from Berliner to the laser disc, suggests this. In rock and roll the spinning disc has other associations, mostly having to do with undirected motion, but there is also the desire to trace a mystic circle around one's own world …Every disc is a microcosm, a twelve-inch or four-and-three-quarter inch world. A shelf of records is a row of possible worlds’ 11

____________________________________________________________________________________

1 This dialogue could be expanded: perhaps it starts with West Side Story, both a Broadway musical in 1957 and a film in 1961 - its DNA can be found in both Tommy and Hommy while the Genesis double album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway in 1974 draws on all of them, absorbing a Puerto Rican lead character into a quintessentially English musical set in New York. Peter Gabriel said ‘it was intended to be an intense story of a young rebellious Puerto Rican in New York who would face challenges with family, authority, sex, love and self-sacrifice to learn a little more about himself. I wanted to mix his dreams with his reality, in a kind of urban rebel Pilgrim's Progress.’ (The Daily Telegraph September 30, 2014).

Rael was also the name of a song on The Who Sells Out. In an interview in the New Yorker, Gabriel highlights the contrasts and cross-pollination he was aiming for in the creation of the main character “Prancing around in fairyland was rapidly becoming obsolete,” he told his biographer, Spencer Bright. He wanted a story about “the most alienated city-oriented person you could find,” acknowledging that Rael would be “the last person to like Genesis.”

2 Lucie Levine, ‘Was Modern Art Really a CIA Psy-Op?’, JSTOR Daily, https://daily.jstor.org/was-modern-art-really-a-cia-psy-op/

3 James E. Dillard, All That Jazz: CIA, Voice of America, and Jazz Diplomacy i n the Early Cold War Years, 3 1955-1965, American Intelligence Journal, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2012), pp. 39-50 While Willis Conover argued that jazz and its musical structures echoed American democracy many disagreed. Dillard notes that ‘In April 1956, with a Dizzy Gillespie tour under way and four months into the Montgomery bus boycott, the White Citizens Council of Alabama, formed to resist desegregation, announced its opposition to jazz. The council called jazz a “plot to mongrelize America” engineered by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).’ Meanwhile the players themselves resisted the blanket propaganda terms of the tours. Dizzy Gillespie, for instance, stated: “I sort of liked the idea of representing America, but I wasn’t going to apologize for the racist policies of America. I know what they’ve done to us and I’m not going to make any excuses.”

4 As early as 1949 there were experiments with radicality and vinyl creation. An image of a white dove by Pablo Picasso was printed directly onto a Paul Robeson 10” shellac disc –‘Chante Pour La Paix’ and privately pressed for the Peace Conference (Congrès Mondial des Partisans de la Paix) in Paris, 1949.

5 Ironically, the music of that album was such a departure from Cortijo’s own past that it was truly celebrated for decades. One critic, Tomas Peña, recounts that ‘Under his leadership, the group rehearsed at a studio in Santurce, Puerto Rico for two months. The sessions attracted Johnny Pacheco, Charlie Palmieri, and Roberto Roena, who, upon hearing the music prophetically commented, “Rafa, you’re screwed! This music is 30 years ahead of its time, no one will understand it.”’ [Tomas Peña, ‘Cortijo’s Time Machine y su Máquina del Tiempo’, Latin Jazz Net - https://latinjazznet.com/reviews/music/essential-albums/cortijo-and-his-time-machine/

6 Robert Farris Thompson, ‘Nueva York’s Salsa Music’, 6.28.75

7 Elodie A. Roy, Media, Materiality and Memory: Grounding the Groove (2016), p.184

8 Kristina Wirtz, ‘Materializations of oricha voice through divinations in Cuban Santería’, Journal de la Société des américanistes, 2018, 104-1, pp160-61

9 Martin Gomez, Interview with Ivelisse Rivera, ‘Ismael era independentista y creía en la libertad de los pueblos’, https://www.salserisimoperu.com/especial-ismael-rivera-ivelisse-maelo-era-independentista-creia-libertad-puertorico-salsa-noticia-12-05-2017/

10 Facebook post, https://www.facebook.com/groups/2359809360769690/posts/5663856377031622/ See also César Colón-Montijo, ‘Specters of Maelo: An Ethnographic Biography of Ismael ‘Maelo’ Rivera’, PhD submission, Columbia University, 2018. Colón-Montijo states that ‘Ecuajei is an expression commonly used to praise the goddess Oyá by practitioners of what J. Lorand Matory (2005) has described as the transnational, transimperial, and transoceanic networks of Black Atlantic Religions. According to Judith Gleason (1987), Oyá is a multifarious deity linked in sacred contexts to ancestry, funerals, secrecy, and the transformation of life from one state of being to another. Oyá manifests in various natural forms such as tornadoes, strong winds, fire, lightning, and buffalo-woman. She also manifests as a wolf-woman and is known as a patron of feminine leadership. Oyá’s devotees voice ecuajei in diverse sacred rituals as a medium to communicate with her.’ Discussing the secrecy and reluctance to discuss some aspects of Ismael Rivera’s life which he encountered during his research César Colón-Montijo concludes that: Ultimately, I propose that people often use secrecy as a means of narrating well-known, endured experiences they find hard to enunciate freely in their day-to-day lives. This secrecy creates a sense of the proverbial, which has sacred connotations that are key to the spectral becoming of Maelo’s voice as well as to the secular devotion he inspires in his afterlife.

11 Evan Eisenberg, The Recording Angel – Music, Records and Culture from Aristotle to Zappa, [1987] 2005, p. 205